Play Jeopardy! online with your friends at Jep!. Choose from past games or make your own. Just share the link to play with friends.

![]() Play a game: https://whatis.club

Play a game: https://whatis.club

![]() GitHub repository: https://github.com/cmnord/jep

GitHub repository: https://github.com/cmnord/jep

If you’re curious to learn more, this blog post explains further rules and how it’s built.

What it does

Real-time gameplay

When you click on a clue on the board, it pops up on the screen for every player at the same time.

Firefox chooses a clue. Safari then buzzes in first.

You all get a chance to read the clue, then race to buzz in. The fastest buzzer gets to answer the clue and gets points if they’re right. If they’re wrong, the buzzers reopen for all other players.

Upload your own games

I made a JSON file format so people can upload their own games. The format allows for an arbitrary number of rounds, categories per round, and clues per category. I hope this flexibility is fun for constructors!

The upload help page describes the format and has a sample file.

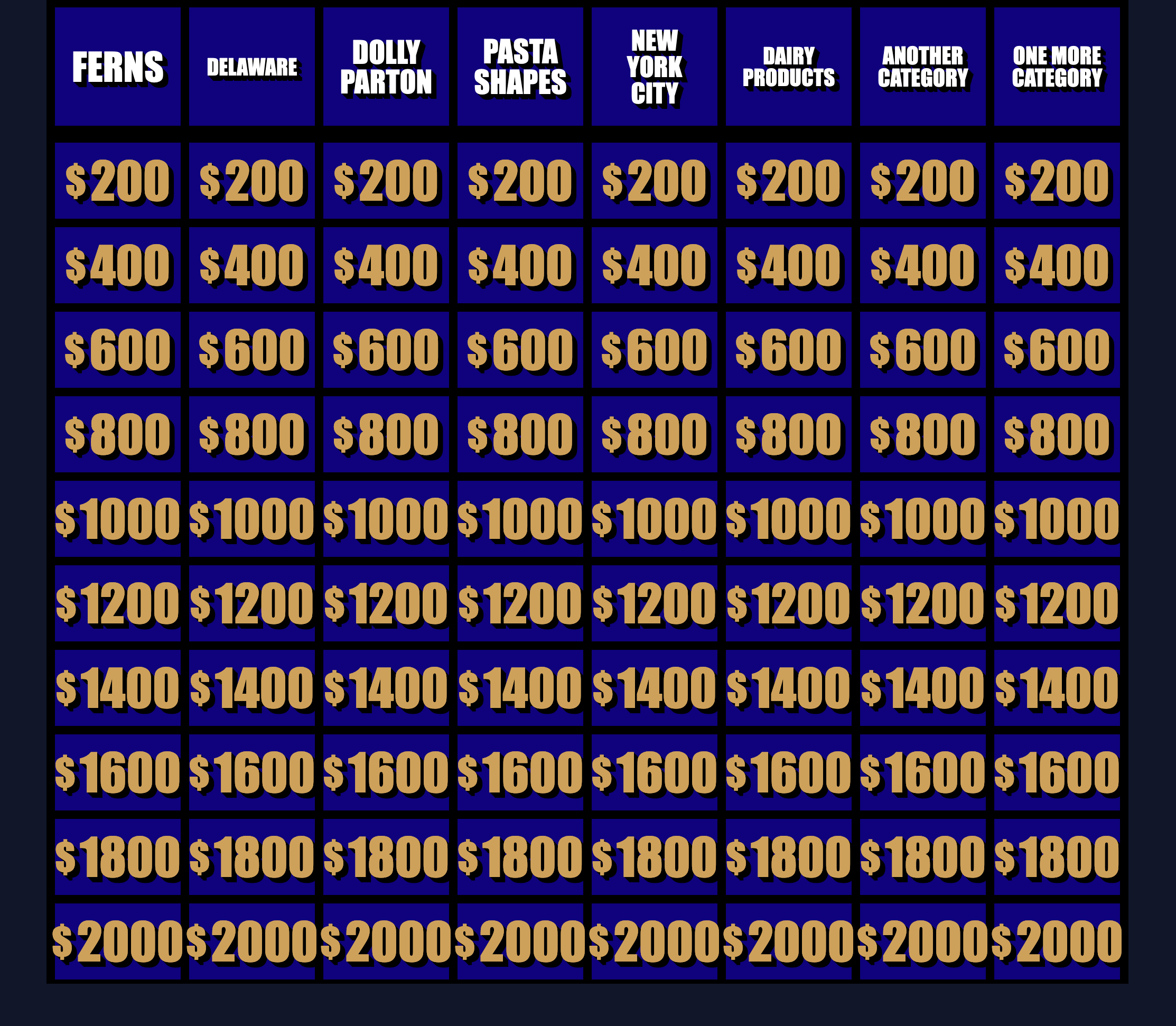

Biiig board

Biiig board

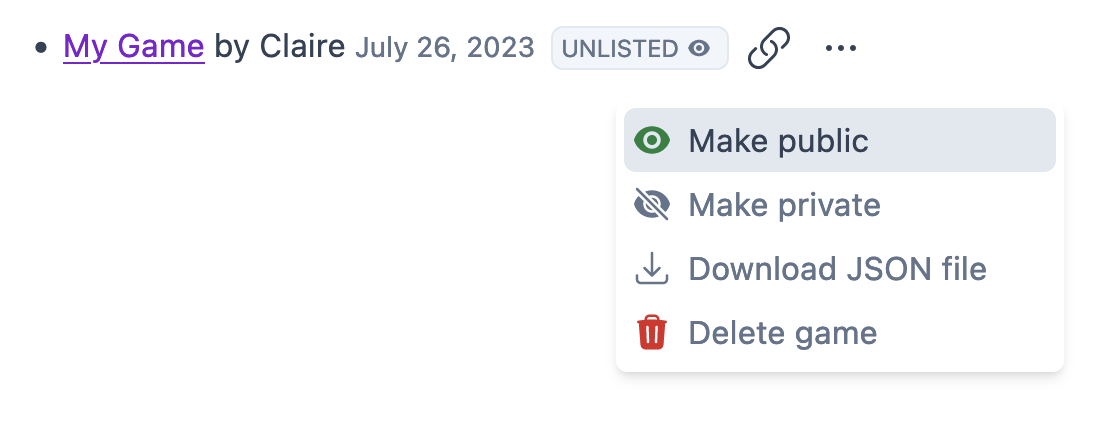

Games can also be unlisted or private so constructors can play their games or playtest draft games without sharing them widely.

Edit game visibility

Edit game visibility

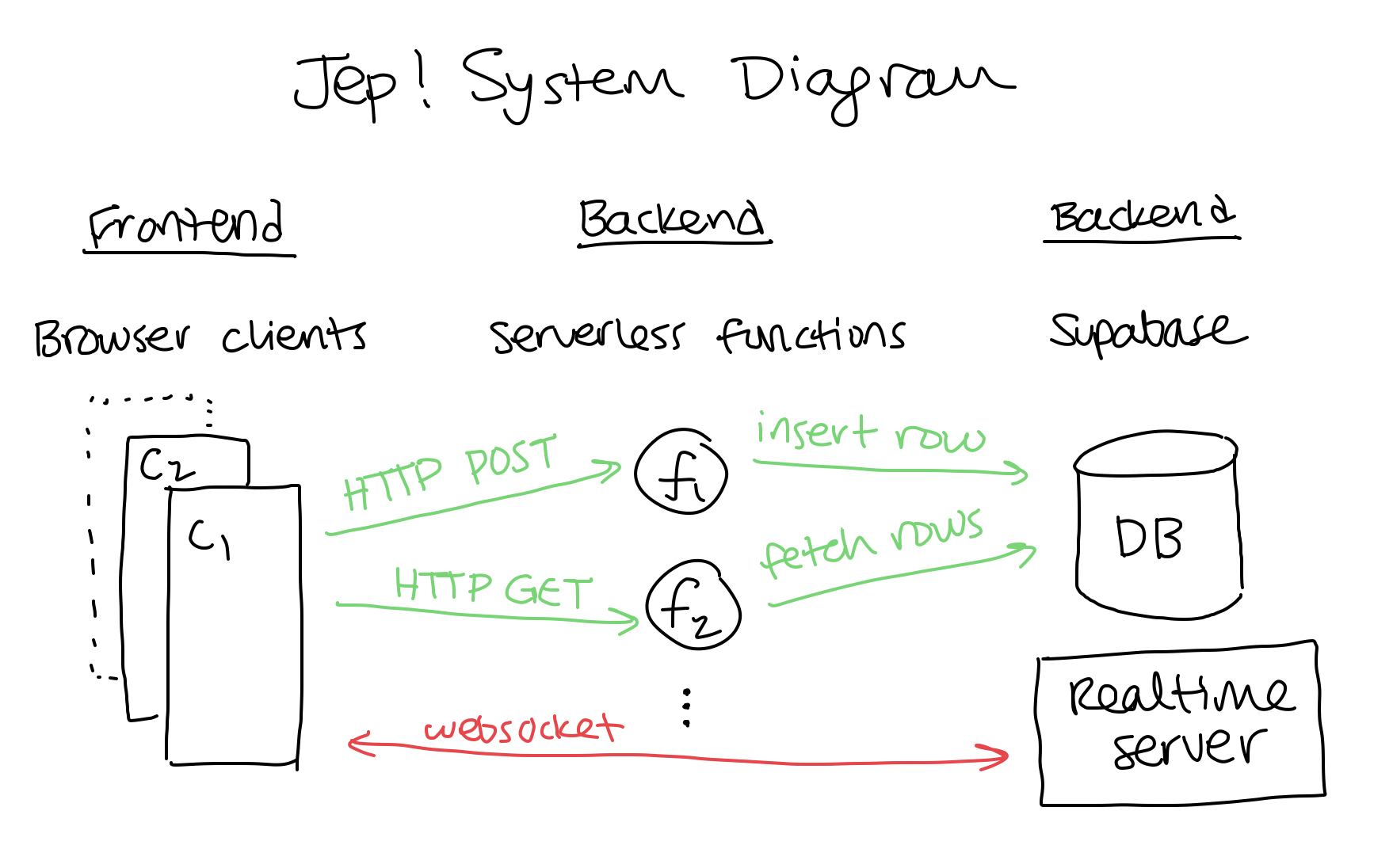

How it’s built

Jep! is built in React using the Remix web framework. The backend is not a persistent server but rather a collection of serverless functions that respond to HTTP requests. All persistent data is stored in a database. The frontend uses websockets to subscribe to real-time updates to the database.

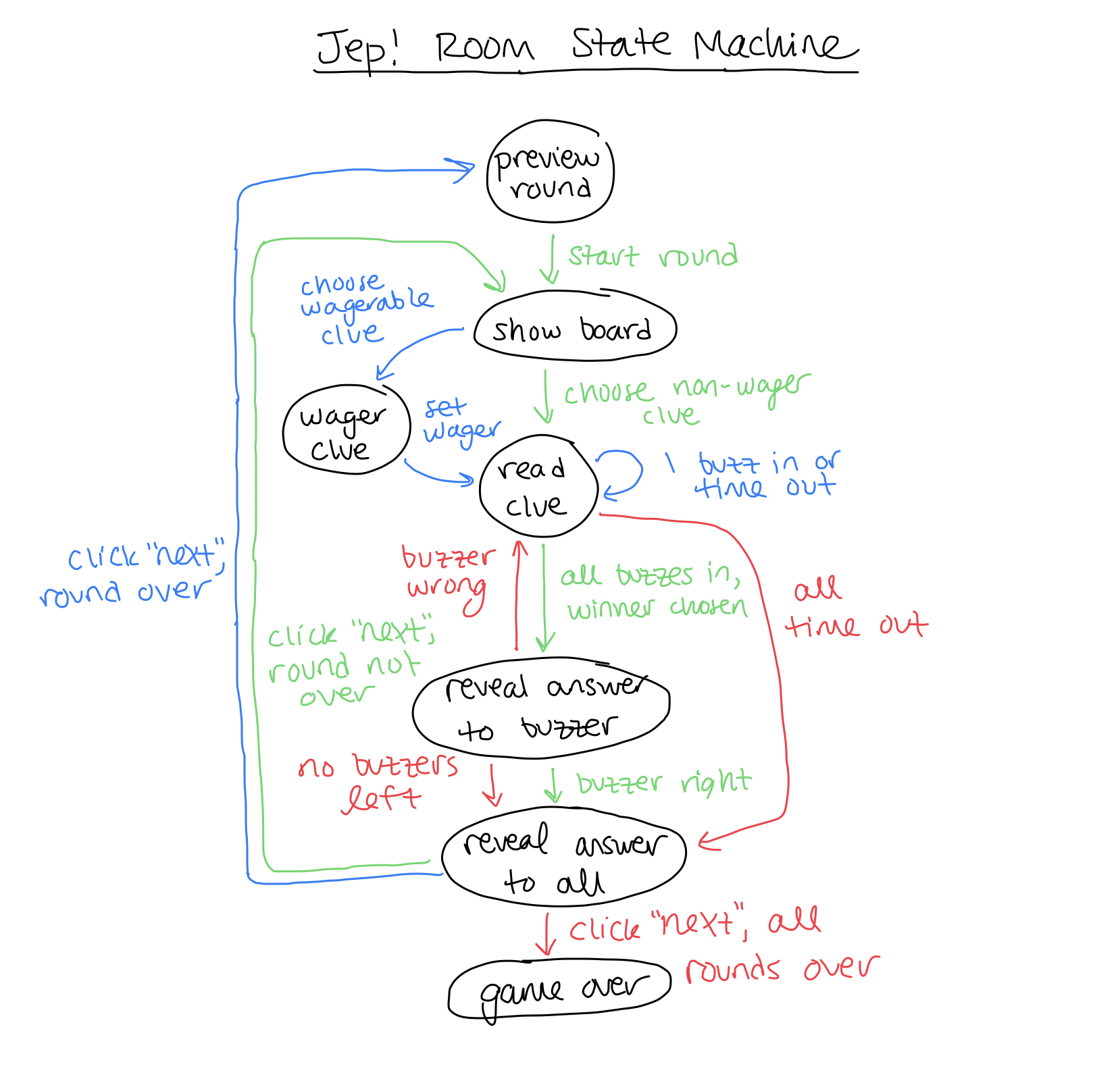

Room logic (state machine)

Choosing a game from the home page creates a new “room”. Every player joins the room from their own web browser. Each player sees the same initial room state (round not yet started, all clues are hidden, everyone’s score is 0, etc.).

Players then take actions in the room that modify the state. For example, a player chooses a clue, then buzzes in to answer.

The room state machine is implemented as a reducer in React.

Simplified room state machine.

Simplified room state machine.

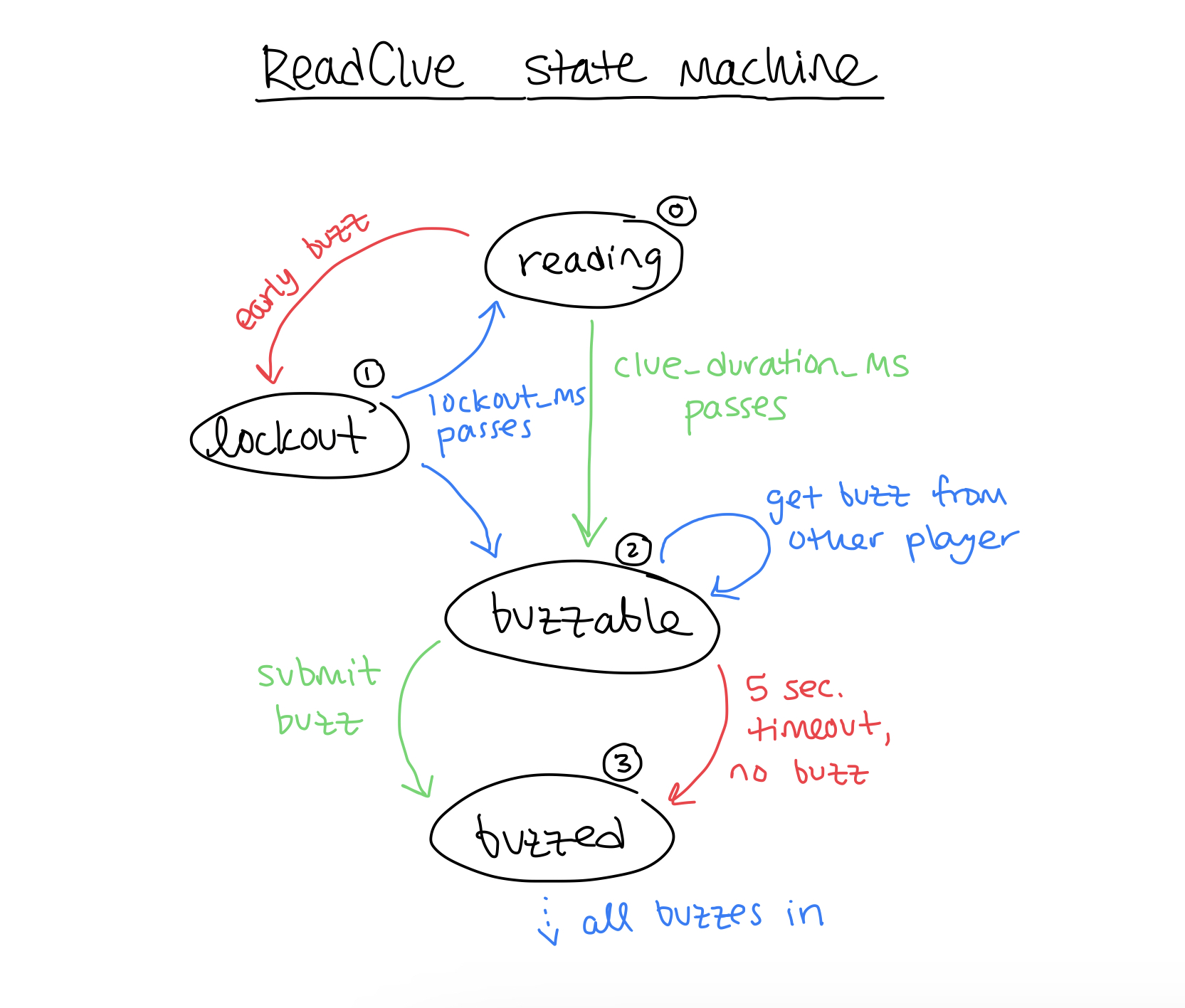

Each room state also has a corresponding client-only mini state machine.

Simplified state machine for a client in the “reading clue” room state.

Simplified state machine for a client in the “reading clue” room state.

Storing room state

Instead of storing the room state itself in one database row, we store the list of actions that have occurred in the room.

- Reads: Fetch all the actions for the room, then apply each action one by one to the initial state to get the current state.

- Writes: When a player takes a new action, the client sends an HTTP POST request to the server, which appends it to the list of actions in the database.

This is called an event sourcing architecture. Writes are fast because they append to the list of actions without worrying about the current state or any other actions. It also makes it easy to replay the actions to compute the state at any point in time.

Each client has a local state machine which computes the current state from past actions.

| ID | Room ID | Action Type | Action Data |

| 1 | 803 | join | {name: player 1, userId: 123} |

| 2 | 803 | join | {name: player 2, userId: 456} |

| 3 | 803 | start round | {round: 0} |

| 3 | 803 | choose clue | {i: 0, j: 0, userId: 123} |

| 4 | 803 | buzz in | {i: 0, j: 0, userId: 456, deltaMs: 351} |

| 5 | 803 | buzz in | {i: 0, j: 0, userId: 123, deltaMs: 489} |

| 6 | 803 | check answer | {i: 0, j: 0, userId: 456, correct: true} |

Example actions table

const state: State = {

type: RoomState.RevealAnswerToAll,

activeClue: [0, 0],

boardControl: 456,

buzzes: { 123: 489, 456: 351 },

isAnswered: [

[{ isAnswered: true, answeredBy: 456 } /* ... */],

// ...

],

players: {

123: {

name: "player 1",

score: 0,

},

456: {

name: "player 2",

score: 200,

},

},

round: 0,

// ... more state

};

State computed from example actions above

Timeout actions + serverless functions

Some actions aren’t really player-initiated, but have to be modeled as such because there’s no persistent server running on the backend. For example, what if no players buzz in within 5 seconds to answer a clue? There’s no server-side timer tracking this, so all the players would be stuck waiting for someone to buzz in.

To fix this, each client submits a “5 seconds elapsed” action after the timeout. Upon receiving any “5 seconds elapsed” message the state machine advances the room state to the next step.

Real-time updates

If Player 1 chooses a clue, how does Player 2 see that clue pop up on their screen at the same time? In other words, how do they read one anothers’ writes in real time without refreshing the page?

The client subscribes to real-time updates from the “actions” table. This opens a websocket connection to the Supabase realtime server. When the actions table receives a new row, the server broadcasts the row to all clients subscribed to that action’s room ID.

The client then receives that action and applies it to its local state machine. This way all clients have a consistent view of the room state.

Example use case from the Supabase realtime page

Example use case from the Supabase realtime page

Designing Jeopardy! without a host

The biggest difference between the show and Jep! is that there’s no host to communicate what’s happening at any given time, keep up the momentum, and check answers. The first two can be addressed with good design, but the last one is trickier.

Check your own answers

I didn’t want to require one player be the host, or make any player check other players’ answers. I also didn’t want to try to make a ~virtual host~ for a couple reasons:

- There are often multiple correct answers to a question, like “aubergine” vs “eggplant” or “Queen Elizabeth” vs “Elizabeth I”. I don’t have an automated way to check this for all questions.

- I don’t want players to have to type, which means the virtual host would have to use speech recognition. I find speech recognition annoying and error-prone.

Having each player check their own answers keeps the game fast-paced and doesn’t put the hosting burden on one person in particular.

Groups also develop house rules for which answers are “close enough” to be correct. Self-checking helps account for more and less strict play styles. However, it’s not as suited to a competitive tournament setting.

Say your guess, then check privately

We keep players honest by having them say their guess out loud to others before checking it. This requires players to join a voice call or the same physical room together.

Here’s an example transcript:

PLAYER 1: Ferns for $600.

**Text: FERNS FIRST EMERGE IN THE FOSSIL RECORD IN THIS PERIOD**

PLAYER 1: [Buzzes in]

PLAYER 1: Hmm... what is the Jurassic period?

PLAYER 1: [Privately sees the answer]

PLAYER 1: Drat!

PLAYER 1: [Marks "incorrect"]

**Buzzers reopen**

PLAYER 2: [Buzzes in]

PLAYER 2: Ah, it's me! What is the Devonian period?

PLAYER 2: [Privately sees the answer]

PLAYER 2: Yep!

PLAYER 2: [Marks "correct"]

**Text: DEVONIAN**

Example game transcript with honest players

With this scheme, you can tell later if someone lied. If they said “Jurassic” was correct, you’d know they lied when the game later showed the answer was “Devonian”.

This design is clunkier than having a host: it’s hart not to blurt out the answer as soon as you learn you were wrong! It adds more cognitive burden during an emotional moment in the game.

Keeping up momentum

I tried to make the visuals as clear as possible, but it’s still sometimes confusing who’s up next to choose the clue or who won the buzz-in. This confusion slows the game momentum and keeps it from moving as snappily as a 20-minute TV show.

I also love using my phone for everything and tried to make the game mobile-friendly, but not everything can fit on phone screens smaller than mine. There’s also a design tension between showing all possible information and controlling what’s shown to keep the stakes high.

These problems are related! I definitely hit the limits of my UI design skills. I would love to get specific feedback or designs that would improve this. For now, I’m happy the game generally works and am ready to move on to other projects.

Conclusion

A major inspiration for Jep! was Down for a Cross, a collaborative crossword website. I wanted to make something similar for Jeopardy! to hopefully give back to the trivia fan community.

I implemented a minimal set of features from Down for a Cross, plus the Jeopardy! game logic. Some fun additions could be:

- Timing the game with a clock

- An in-browser puzzle creator instead of just JSON files

- Coryat score tracking

- …And more!

Thank you to all the playtesters who gave great feedback! Your insight into my fundamental design problems kept me awake at night. Thanks in particular to Alex, Jynnie, Tommy, and Neil, as well as the NCSJ, JJSR, MJKT+, and GACJI playtest groups.

I hope people enjoy playing Jep! and I’d love to hear any feedback or ideas for improvements. Play a game here and check out the code here!